Evidence: Here is how our culture kills mothers, especially teenage mothers!

In Uganda, 15-18 mothers, including teenage mothers, die everyday due to issues arising from pregnancy, during labor and delivery, and few weeks after delivering! In general, our current maternal mortality ratio stands at 336 per 100,000 live births! While there has been some progress in reducing this, the number is still very high. But wait! Which age group is dying?

READ THIS TOO: Policy related factors affecting maternal health

Basically, teenage mothers form a significant part of all mothers in Uganda. Therefore, when we talk of maternal mortality, we are roughly talking about teenage mothers’ deaths (more than 17% of the 333/100,000 maternal deaths happen in adolescents)!

Actually, suggests public health scholars, reducing the number of teenage mothers would ultimately reduce our maternal mortality. Sadly, our national teenage pregnancy stands at 25%, with some areas at about 40%! Teenage mothers are dying!

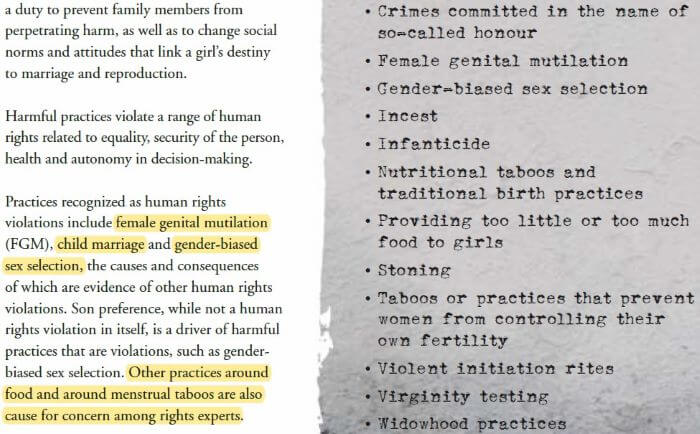

Many factors are contributing to teenage mothers mortality. From unfair cultural practices, for example, forced marriage, female genital mutilation, incest, and others to the practical obstetric complications that happen most with young mothers, teenage mothers are paraded into their death (UNFPA, 2020). And all the above are tied onto culture as illustrated in the 2020’s document regarding world’s population status! To be exact, let us see how culture is killing mothers, most especially, the young teenage mothers!

Cultural factors sending teenage mothers into death!

Many cultural factors have been linked to increased adolescent pregnancy and consequent abortions and maternal deaths. For example, World Health Organization-WHO (2018) points out that the pressure to prove fertility or marry at an early age in some societies leads to early pregnancy, unsafe abortions and maternal deaths.

A 2009 study by Sekiwunga and Whyte cited that early marriage and pregnancy have been acceptable norms in Uganda’s society despite the current policy efforts to avert them. In their qualitative study, many females reported how their parents and relatives pressurized them to settle in marriage and parenthood while still young. The researchers quote one girl in these words: “Another reason is culture because if a girl does not marry at 14 or 16 years, it becomes a curse to the family” (Sekiwunga and Whyte, 2009).

In other words, forcing girls into marriage at an early age is sending them into death! Many studies show how obstetric complications and death are more common with girls who become pregnant at tender age than their counterparts (Ganchimeg et al., 2014). In one study, teenage mothers have higher chances for obstetric complications and death in pregnancy just as very old women! And in another study, girls who are below 15 years are 5 times more likely to experience dangers!

The tendency to neglect contraception use is another important cultural factor responsible for increased maternal deaths among adolescents. In rural Nepal, a 2012 study by Anifah and friends found out that, culturally, family planning is not welcome especially when it comes to young girls below 19 years (Anifah et al., 2012). According to this study, ‘although the majority of the respondents knew at least one method of contraception, less than 1% had used it before their first pregnancy’. This resonates well with the low utilization of family planning methods here in Uganda, especially among the young women; contraceptive unmet need among adolescents is 30% (UDHS, 2016).

I remember a discussion about introducing and allowing family planning access in primary schools here in Uganda; IT WASN’T A WELCOME MOVE! In general, family planning use, especially by teens is still looked at with a frown! However, many scholars argue that at least information should be readily available.

READ THIS TOO: Decreased Immunity in Pregnancy and How to Go about It!

With no proper access to family planning, young women begin giving birth at tender age into their 40s, increasing the odds for their deaths. Additionally, there is no proper spacing, and limit on the number of children, implying more complications for the teenage mother and the children she produces.

A 2017 study by Krugu and friends in Ghana revealed that, in most African communities, sexuality and sexuality education are taboos. In their words, the researchers reported that ‘sexuality remains a largely taboo topic for open discussion and sex education in schools seems limited to abstinence-only messages’ and thus open communication regarding sexuality is needed (Krugu et al., 2017). This is not different when we consider Uganda’s context.

In a 2015 study on sexuality communication between adolescents and parents in Uganda, Muhwezi and friends found out that sexuality communication was rarely possible between parents and children and this was even rarer if the parent in consideration was a father. According to the report, ‘fathers were perceived by adolescents to be strict, intimidating, unapproachable and unavailable’. In addition, if it (sexuality communication) ever happened, it was more about sexually transmitted diseases and body changes and rarely about sex, pregnancy, condoms, and relationships (Muhwezi et al., 2015).

Intolerance of sexuality and sexuality education in Uganda’s culture explains the tension that has always remained between accepting and not accepting sexuality education in schools, a challenge that Uganda’s government responded to by drafting and releasing national sexuality framework 2018 (Ministry of Education and Sports, 2018), which was, to an extent, rejected or questioned by Ugandans, especially religious and cultural leaders (LaCroix, 2018; Crux, 2018; New Vision, 2018). This framework isn’t yet in action!

With COVID19 and the consequent lockdown, teenage pregnancy soared to more than 7000 nationally. There have been reports of increased child abuse, and accessing reproductive health care services has been a struggle across the globe. All of this means many girls have been positioned for obstetric risks and possible death!

READ THIS: How far is Uganda with Gender Equality?

Some researchers have cited unequal gender power relations and poor education of girl child to be cultural factors responsible for adolescent pregnancy and resulting complications (National Adolescents Health Strategy 2011-2015, p. 11). In the recent systemic review by Yakubu and Salisu (2018), it is reported that most societies, especially when situations demand a decision to choose between schooling a girl or male child, opt to take male children to school at the expense of female children. In the same report, societies are reported to consider male children as responsible and deserving to control family resources and not females (for example, family inheritances are trusted with males and not women).

These practices (failing to educate girls and not trusting them with resources) make them (girls) weaker and not empowered enough to take on their reproductive challenges, and are exposed to early marriages, pregnancies, and abortions. Besides, adds Uganda’s Ministry of Health (2016), most young women lack capacity to make decisions regarding their lives in most relationships leaving power and decisions in the hands of men.

So, what is your culture on education of girls and boys? When conditions become tough, who drops out of school first? How about property inheritance? How about decision-making in our homes? Who decides when and how to have the next child or when and where to go for health services, especially maternal services? All of these issues are affected by our culture, and, in most cases, negatively! So, is our culture not killing mothers?

Another important factor that is tied onto culture, norms and values is that of family history of adolescent pregnancy. In 2011, Akella and Jordan did a study on ‘Impact of Social and Cultural Factors on Teen Pregnancy’ in one of the American states and their results revealed that there was increased risk of adolescent pregnancy among young women whose mothers or siblings had gotten pregnant when young (Akella and Jordan, 2011).

In Uganda, Akanbi, Afolabi and Aremu identified similar findings in their 2016 study at Naguru teenage center here in Kampala. In their own words, the researchers reported: ‘Teenagers whose siblings were sexually active…were more likely to get pregnant. Teenagers whose siblings ever got pregnant were more likely to get pregnant’ (Akanbi, Afolabi and Aremu, 2016).

Conclusion cultural factors and teenage mother death

The UNFPA’s report on state of world population 2020 is titled ‘AGAINST MY WILL: Defying the practices that harm women and girls and undermine equality’. In this document, 20 practices that are dangerously sending our young women to ‘hell’ are listed, and discussed in details. The question is, which is one is your sin? See the attached screenshots below!

All these practices, most of them woven into our culture and seen as normal and acceptable, are making it hard for mothers, especially teenage mothers, to thrive! Preventing them is a great service to all women, and mankind.

REFERENCES

John Kingsley Krugu, Fraukje Mevissen, Meret Münkel & Robert Ruiter (2017). Beyond love: a qualitative analysis of factors associated with teenage pregnancy among young women with pregnancy experience in Bolgatanga, Ghana, Culture, Health & Sexuality, 19:3, 293-307, DOI: 10.1080/13691058.2016.1216167.

Ministry of Education and Sports-Uganda (2018). National Sexuality Education Framework 2018.

Muhwezi et al. (2015). Perceptions and experiences of adolescents, parents, and school administrators regarding adolescent-parent communication on sexual and reproductive health issues in urban and Uganda. Reproductive Health (2015) 12:110

Fulatul Anifah, Atik Triratnawati, Herlin Fitriana K and Djaswadi Dasuki (2012). Sociocultural factors influencing adolescent pregnancy in rural Nepal. 14(2):101-9 · April 2012

Ibrahim Yakubu and Waliu Jawula Salisu (2018). Determinants of adolescent pregnancy in

sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review.

Richard Sekiwunga and Susan Reynolds Whyte (2009). Poor Parenting: Teenagers’ Views on Adolescent Pregnancies in Eastern Uganda. Afr J Reprod Health 2009; 13[4]:113-127

Akella, D. and Jordan, M. (2011). Impact of Social and Cultural Factors on Teen Pregnancy. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice Volume 8, Issue 1, Spring 2015, pp. 41 – 62

Akanbi F., Afolabi KK. and Aremu AB (2016). Individual Risk Factors Contributing to the Prevalence of Teenage Pregnancy among Teenagers at Naguru Teenage Centre Kampala, Uganda

World Health Organization-WHO (2018). Global health estimates 2018: deaths by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 2000–2018. Geneva: WHO; 2018

World Health Organization (2014). Meeting report: consultation on methods for improved global sexually transmitted infections estimates. November 11±12, 2013, Geneva, Switzerland. Geneva

Ministry of Health (2016). National Communication Plan for HIV Testing Services. STD/AIDS Control Program. Kampala, Uganda

Uganda Bureau of Statistcs (UBOS) and ICF (2017). Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2016: Key Indicators Report. Kampala, Uganda: UBOS, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: UBOS and ICF

Ganchimeg, T., Ota, E., Morisaki, N., Laopaiboon, M., Lumbiganon, P., Zhang, J., … & WHO Multicountry Survey on Maternal Newborn Health Research Network. (2014). Pregnancy and childbirth outcomes among adolescent mothers: a W orld H ealth O rganization multicountry study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 121, 40-48.

Ministry of Health (2010). National Home-Based Care Policy Guidelines FOR HIV and AIDS; august 2010

Uganda AIDS Commission (2015). National HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan 2015/2016- 2019/2020, An AIDS free Uganda, My responsibility! Uganda AIDS Commission, Republic of Uganda.