The History of PHC (Part 4): Introduction of GOBI-FFF, Child Survival Revolution, & Kick-out of Comprehensive PHC!

In part 1, we opened ourselves to events before Alma Ata Declaration and noted life-time heroes and scholars who bargained for ‘health for all’, efforts that culminated into Alma Ata Declaration and the official birth of Primary Health Care. In Part 2, we deeply explored the Alma Ata Declaration, the official birth of PHC or ‘health for all by 2000’. In part 3, we looked into criticisms and schemes that followed the declaration, and the rise of a different version of PHC, Selective Primary Health Care (SPHC). Good.

In today’s article, we are exploring debates that followed the proposal of SPHC and the related concepts of GOBI-FFF, Child Survival Revolution, and UNICEF’s hand in such debates.

READ THIS TOO: The History of PHC (Part 1): Before Alma Ata Declaration!

We have already established GOBI and GOBI-FFF in full, haven’t we? Well, in case you didn’t grasp it anywhere or you wanna remind yourself, here we go: GOBI stands for Growth monitoring, Oral Rehydration Therapy-ORT, Breastfeeding and Immunization. And when we add the three Fs, we have GOBI-FFF, with Family planning, Female literacy, and Food supplementation added onto our GOBI abbreviation. The rest remains the same.

But how did we reach here? Read on!

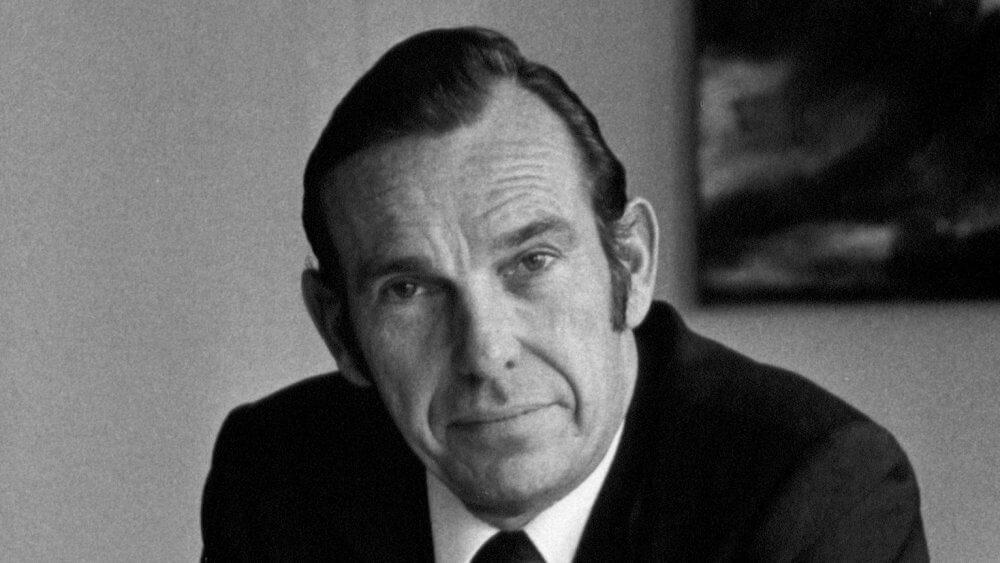

GOBI-FFF and James Grant, UNICEF’s director

Usually, GOBI-FFF and selective PHC are attributed to UNICEF but that is not the case. UNICEF, just like other institutions (USAID under John J. Gillian, Canadian International Development and Research Center under Maurice Strong, Robert S. McNamara-1968 World Bank President) took part in organizing and attending the Rockefeller Foundation’s conference.

According to Adamson and Tacon et al., (2001) and Cueto (2004), UNICEF was influenced by the conference and Warren and Walsh’s paper findings, and suggested interventions. In January 1980, James Grant was appointed as the executive director of UNICEF and held the position up to 1995.

According to Cueto (2004), Grant (himself a son of a Rockefeller Foundation medical doctor) believed that international agencies had to do their best with finite resources and short-lived local political opportunities. This meant translating general goals into time-bound specific actions. During his leadership, asserts Marcos Cueto, UNICEF started to back away from a holistic approach to primary health care.

In few years that followed (probably 1982), Grant organized a UNICEF book (The State of the World’s Children) that proposed ‘Child Survival Revolution’ (an effort started by UNICEF but joined by others between 1982-1990s) to reduce child mortality in the developing world. In the book, he explained and emphasized the four inexpensive interventions contained in GOBI (Cueto, 2004).

Cueto (2004) says that other agencies later added the tripe F (FFF) onto the acronym GOBI, making GOBI-FFF (Growth monitoring, Oral Rehydration Therapy, Breastfeeding, Immunization, Family Planning, Female Literacy, and Food Supplementation). However, a deeper look into UNICEF’s book championed by the then executive director, James Grant, clearly reveals all the above elements of GOBI-FFF (UNICEF, 1980).

Following this launch of GOBI or selective PHC by UNICEF, more debates followed for about 2 more decades. According to Cueto (2004), Mahler had even attended the Rockefeller Foundation conference and he did not show any opposition to the new measures that were being forwarded. Instead, affirms Cueto, he asked WHO assistant general to maintain good relationship with UNICEF and its leaders and push forward for such ‘noble’ causes.

WHO (some of its members) tried to respond to the accusations that PHC was broad and its goals unmeasurable by publishing various papers (for example, the 1980’s indicators for monitoring progress towards health for all and health for all goals and the 1981’s development of indicators for monitoring progress towards the health for all by 2000) but these were still not paid attention to. The debates went on.

READ THIS TOO: The History of PHC Part 2: Alma Ata Declaration!

Accusations by GOBI-FFF and PHC Advocates

Generally, advocates of Comprehensive Primary Health Care (CPHC) accused those of Selective Primary Health care (SPHC) for being narrow and isolating health from the general socio-economic lives of people. Besides, interventions like growth monitoring and breastfeeding were cited to be unfit.

Growth monitoring was said to be complex and mothers (illiterate) in developing countries unable to do the measuring, and breastfeeding was accused of being a burden to already undernourished mothers (Cueto, 2004).

However, Sheefild (1979) asserted that accusations against breastfeeding were wrong and being promoted by companies like nestle that wanted people to do bottle-feeding with infant formulas.

But even if this was true (that Nestle was advocating for bottle-feeding), as health advocates asserted, many people were not having access to safe water, to later use for bottle-feeding. It would still be a failure. Indeed, studies show that introduction of formulas and promotion of bottle-feeding led to infant deaths as early as in 1950s (Wickes, 1953).

In other words, whether breastfeeding got chosen over bottle-feeding or bottle-feeding won the race, there was need for other factors before registering any success, namely, safe water and good nutrition for either breast-feeding or bottle-feeding! This meant that true proponents of Comprehensive PHC cared about the social aspect of the debate and not necessarily any of the specific interventions.

SPHC advocates, especially donors, this truth; that either way, there was need for proper nutrition and safe water supply.

On the other hand, immunization improved and infant mortality rate reduced in developing world (for example, Colombia). It is said that immunization improved from about 20% to 84% coverage in some countries, for example, Turkey. Yet this did not stop the debate.

The tensions between WHO and UNICEF grew stronger (especially following UNICEF’s commitment to GOBI in 1980s). SPHC advocates accused Mahler and WHO for being idealistic instead of technocratic, having no clear funding mechanisms as compared to Malaria eradication program of 1950s, and having broader goals with unspecific outcomes. We will deeply explore these tensions, accusations, and debates around these two approaches in the next article.

READ THIS TOO: The History of PHC Part 3: The introduction of selective primary health care

The embrace of GOBI-FFF & the start of the end of CPHC

Many donors and agencies later preferred the short-term goal-specific interventions and, in addition, most developing nations were suffocating on foreign debts and economic recession and were scared by fund withdraws by donors and thus started to embrace the ‘supposedly’ cheap GOBI-FFF interventions (Cueto, 2004). This marked the beginning of the ‘end’ of pure CPHC.

This context is similar to the current structural adjustment program employed by World Bank and IMF while giving loans to developing nations, and the terrible consequences of such approach to social lives.

This context also provided a good environment for ‘medical emperors’ (elitism) who didn’t want to lose their privileges, work in rural settings, and experience the ‘hard sacrifices’ for PHC programs.

Mahler continued his personal crusades in 1980s though he was usually alone. According to Cueto (2004), Carl Taylor (one of Mahler’s friends and advocate for PHC) left John Hopkins and moved to China, Tejada De Rivero (Mahler’s assistant at WHO) moved permanently to Peru.

Dr. Halfdan Mahler leaves WHO, GOBI-FFF takes roots!

In 1988, Dr. Halfdan T. Mahler ended his service at WHO and Hiroshi Nakajima was elected as the new director general. PHC, which had remained active behind the scene, especially with support of WHO under Mahler now had to cease making news!

According to Marcos Cueto, Nakajima wasn’t charismatic or great as his predecessors and his leadership at WHO marked the end of the first period of PHC until, in 1997, when Pan American Health Organization (now, a regional WHO in America) proposed a new target, ‘Health for All in the 21st Century’ (Cueto, 2004).

According to a biography about Mahler prepared and published by Radboud University, he later joined International Planned Parenthood Federation in London where he served as a director until 1995.

In 2008, in his address to the World Health Assembly in commemoration of 30 years since Alma Ata Declaration, Mahler (the then 85 years old), instead of expressing regret over the ‘Health for All by 2000’ agenda, re-asserted his belief in social justice approach and criticized vertical biomedical public health interventions for seeing humans as medical consumers. In his own words, Mahler said, “visionaries have been the realists in human progression” (Radboud University, 2018).

Mahler died on 14th December 2016 at 93 years old. See more here.

In part 5, we will explore the debates around GOBI-FFF or SPHC and CPHC. For now, chao-chao!